Future State and iSpirit have co-written the Data Empowerment Starter Kit and would appreciate your feedback on it. Please take a few minutes to offer your input here.

Questions are also below and can be ranked from strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree:

- This starter kit provides information that is new to me

- This starter kit is a useful overview of data sharing requirements

- I will share this starter kit with my professional network (if so, who specifically?)

- I would like to see more materials from Future State and iSpirt (if so, what topics?)

- What do you appreciate most about this starter kit?

- What do you not appreciate about this starter kit?

- Do you have any general feedback or advice to Future State and iSpirt?

Thank you for your feedback.

1 About this Kit

Liberating Data, Empowering People

As more people and more devices come online, personal digital data is growing at exponential rates as individuals generate rich data histories about themselves.

The way in which personal digital data is governed (managed, accessed and shared) will determine whether personal data — an individual’s “data endowment” — is a liability, at risk of privacy breaches and misuse, or an asset that can be leveraged for improved access to healthcare, credit, and other services.

We believe data governance will significantly determine the arc of socio-economic development over the coming decades.

Accordingly, policymakers are being forced to grapple with how to appropriately balance seemingly competing priorities such as safeguarding personal privacy, promoting social goals, ensuring competitive marketplaces and fostering innovation. These imperatives raise fundamental questions about data ownership, access, and control as well as who should reap the benefits of personal digital data.

The ability of individuals to safely share their own personal data to access improved public and commercial services is critical to ensuring data assets become a force for good. If governed well, data can close capability gaps in government, foster small business growth, and empower people to access life-enhancing services. It can drive inclusive growth and encourage more people to participate in the data economy.

Personal data sharing for empowerment should be architected such that the system creates value for individuals and gives them meaningful influence over decisions that impact their lives. [1] Data can empower individuals in several ways. First, control over data increases individual capacity to act independently, and make choices of their own free will. In other words it increases agency. If users are incentivised to share their data in a safe and secure manner, it avoids risks of being exploited or oversharing. Second, private companies can use data to improve the customer experiences. They can give personalised experiences, understand what is working for users, respond to user needs and map the company’s forward journey. [2] Similarly, governments can use personal data to target individuals more effectively and benefits and subsidies in an efficient manner. All of this can lead to individual empowerment.

Therefore, the focus of this starter kit is how to safely and responsibly “liberate data” and thus empower individuals.

We focus on the policy, institutional, and technological requirements for safe data sharing solutions that can scale to national levels. The starter kit also focuses on the users, and how to engage and empower them through the process designing and using data sharing. While we touch on critical readiness factors, we point readers to outside resources to learn more.

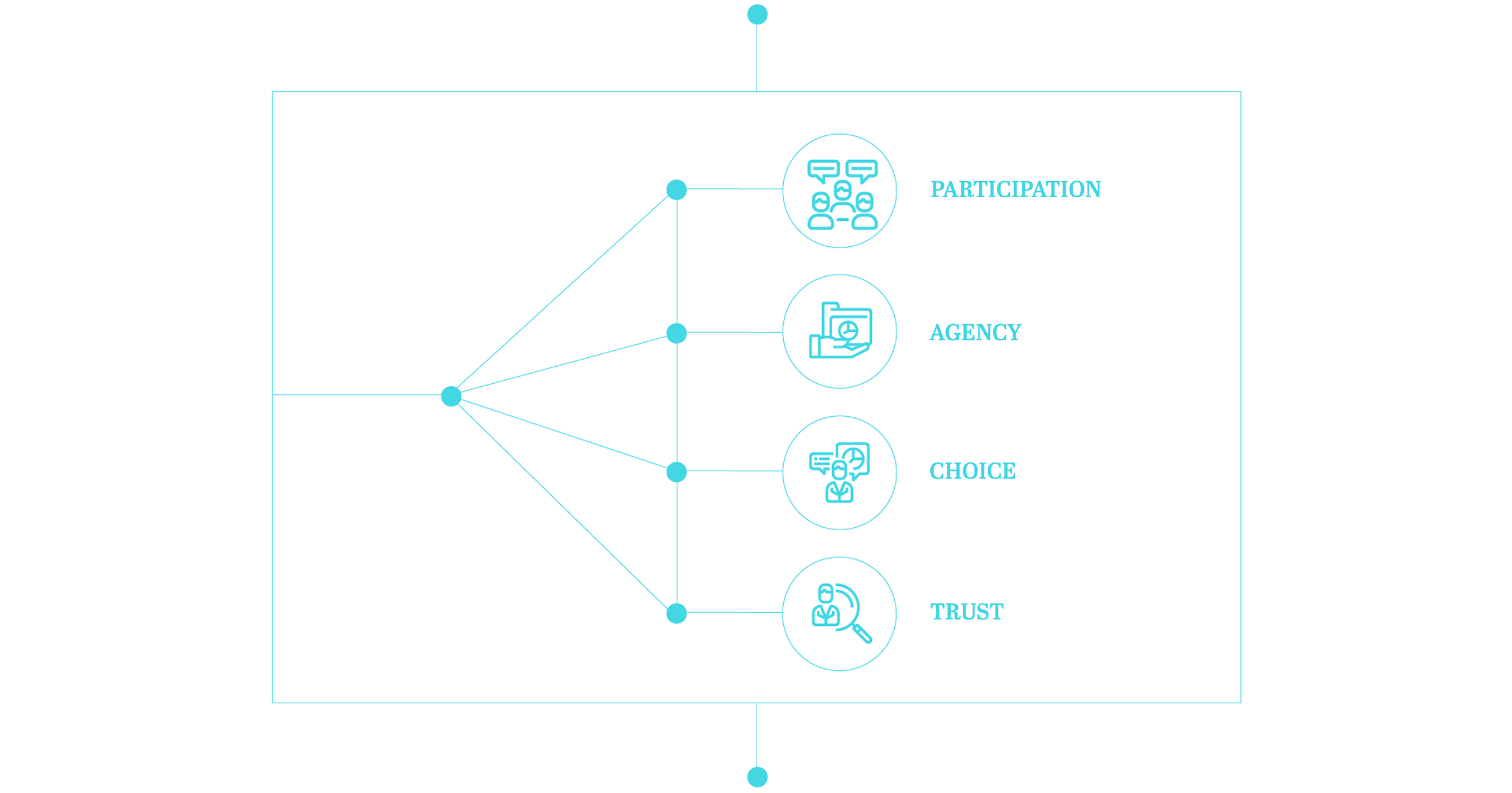

PACT Framework: Empowering Digital Economies

The Future State PACT framework outlines the attributes of a digital economy must exhibit for individuals — particularly the marginalized segments of society — to be most empowered. While many other indices measure the extent to which an economy has “digitized,” we focus on the long-term attributes that arise as a consequence of digitization.

An empowering digital economy is one that maximizes:

Participation, whereby all individuals can and do access public and commercial digital services that better their lives;

Agency, whereby participants in the digital economy have more agency over their data, easy ability to transfer their business to other service providers, and means by which to hold data controllers accountable;

Choice, whereby the private sector increasingly competes and innovates to offer digital products/services across consumer segments; and,

Trust, whereby participants have the information, protections, and skills to discern the reliability of information given to the, claims and quality of data is verifiable, and there are appropriate systems for voicing and addressing concerns.

We believe that any successful digital economy must reflect these values, even if in different forms and gradations, in its policies, technology and institutions to ensure the individuals are protected, empowered and willing to engage with the digital economy.

About the Data Empowerment Starter Kit

This starter kit addresses three attributes of the PACT framework — agency, choice, and trust — that can be enhanced with a robust data sharing architecture allowing individuals control over their data and choice with respect to who accesses their personal data.

Many countries today are introducing legislation and regulation to give individuals more rights over their personal digital data. However, too often, these are being introduced in the absence of technological systems and institutions that make secure data ownership and sharing possible at scale.

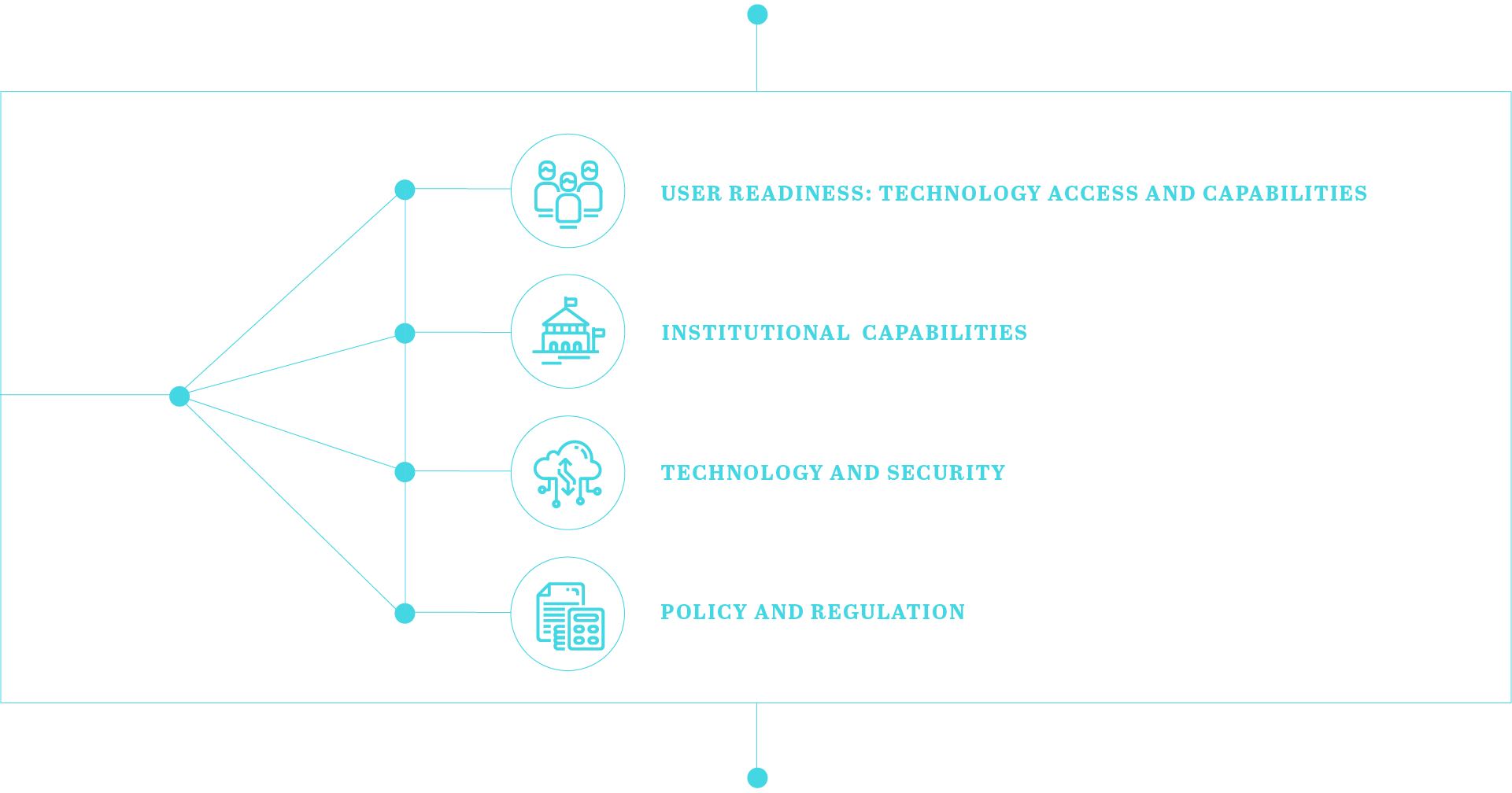

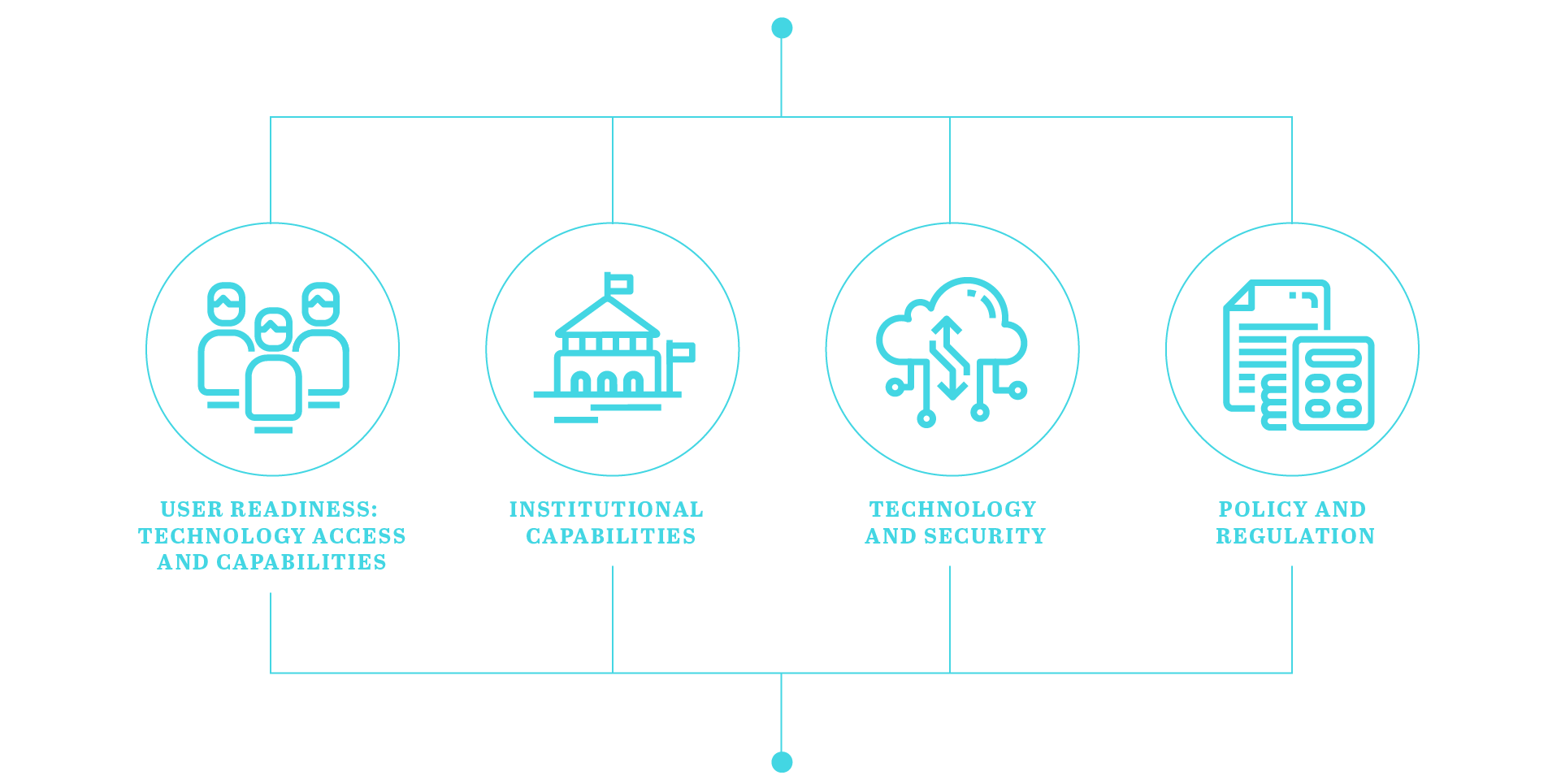

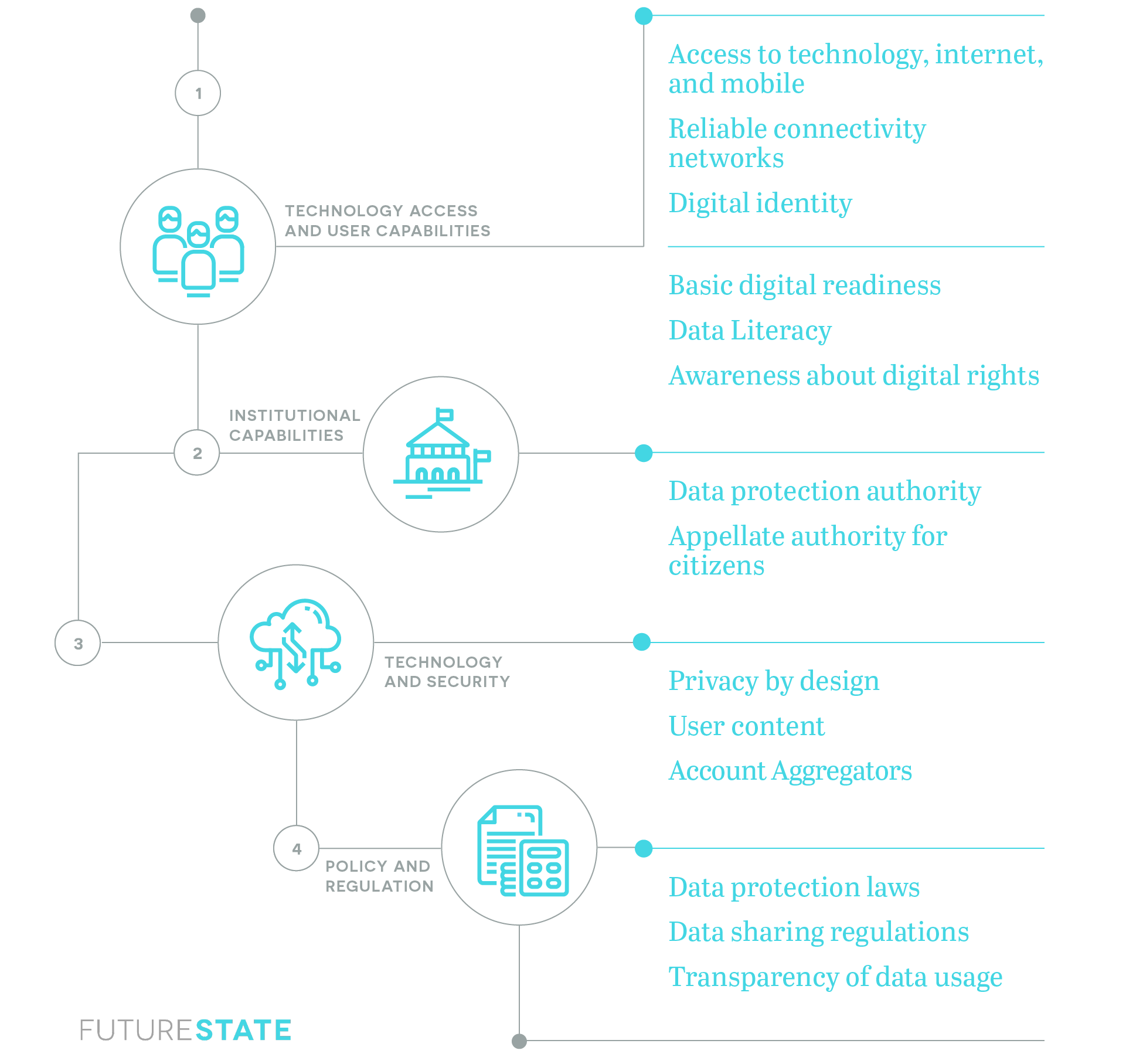

This starter kit suggests governments pursue a 4-pronged path toward data sharing solutions:

India and Estonia represent global leaders in introducing national data sharing solutions so this starter kit draws largely from those experiences.

Given the robust discourse on policy and regulation related to data privacy and data security standards, we do not delve deeply into these realms. These are critical components of trust-enhancing data sharing for empowerment and urge readers to go to several resources such as these overviews of global data protection laws and regulations, for more information.

Further, in this starter kit, we are only concerned with personal data, that can be generated, owned and shared by individuals and used for their empowerment. This document does not deal with open or aggregated that may also be used to empower individuals but needs to be regulated and managed differently.

Finally, it must be stated that the intent of this document is not to prescribe a “how-to” but rather offer a framework of the key considerations related to a holistic approach to data empowerment that can be adapted to different contexts and priorities.

India and Estonia represent global leaders in introducing national data sharing solutions so this starter kit draws largely from those experiences.

Given the robust discourse on policy and regulation related to data privacy and data security standards, we do not delve deeply into these realms. These are critical components of trust-enhancing data sharing for empowerment and urge readers to go to several resources such as these overviews of global data protection laws and regulations, for more information.

Further, in this starter kit, we are only concerned with personal data, that can be generated, owned and shared by individuals and used for their empowerment. This document does not deal with open or aggregated that may also be used to empower individuals but needs to be regulated and managed differently.

Finally, it must be stated that the intent of this document is not to prescribe a “how-to” but rather offer a framework of the key considerations related to a holistic approach to data empowerment that can be adapted to different contexts and priorities.

Finally, it must be stated that the intent of this document is not to prescribe a “how-to” but rather offer a framework of the key considerations related to a holistic approach to data empowerment that can be adapted to different contexts and priorities.

2 The Basics

What is Data?

Before categorizing data, it is important to understand the nature of data currently.

The data economy’s value chain is complex and individuals are not the only actors at either end. The creation of personal data would not be possible without the platforms provided by technology companies, and governments and businesses also represent significant demand drivers. Simply put, data is not just owned by individuals and no one stakeholder has absolute rights on it. Therefore, it is important to categorize data, and regulate it accordingly.

Potential categorization of digital data

Before defining an approach to data sharing it is essential first to develop a landscape and categorization of different types of data. There is no global standard for data categories because context matters. Some data can be considered highly sensitive in one country but not in another, for example.

Further, different data types need to be regulated according to sensitivity levels. Certain categories of data may have elevated protections that prohibit their processing, while others might be more easily accessible. It is imperative to clearly define data at the beginning and then develop solutions for personal data keeps sensitive information most protected.

Along with defining types of data, another part of categorization is to streamline and standardize the form in which data exists and how it will be shared. Today, even in the most advanced data economies, such as India, various ministries within the government and corporates are using and storing data differently. This creates friction in the sharing process and makes it cumbersome for all stakeholders to participate productively.

Beyond data generated on platforms, categories should also represent derived data, which this includes inferences made based on multiple sources of data such as a credit score or voting predictions. Derived data is created through algorithms applied to personal data, such as it is possible to ascertain political views through online book purchases, or sexual orientation through page likes on social media.

The conversation on definitions of personal data have grown in the last few years. The European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has paved the way for many countries. In 2018, several countries have developed regulations for personal data. To see how countries define personal data please follow these links:

It is important that countries define their own categories of data and organize the levels of sensitivity and standardize data before designing the data sharing framework

Checklist

- Conduct stakeholder meeting to build support for data categories

- Organise them by levels of sensitivity and mark out the ones relevant for data sharing for empowerment

- Publish data categories and their permissions widely and consider charter of citizen rights in a data economy with a focus on personal data rights

Why Share Data?

National solutions to using data for empowerment are emerging for two distinct reasons.

Most practically, these can solve specific “pain points” that arise when data is locked in different databases, in different forms, and in ways that make it difficult for data to be migrated from one place to another. Often the process of accessing one’s data involved a long process including account user names and cumbersome passwords to enable data scraping or, worse yet, navigating lengthy phone operators or lines to receive physical document of records.

Second, and just as importantly, data sharing for empowerment solutions are a means to rebalance the power dynamics of data economies, which tend to skew toward commercial platform providers and/or the state at the expense of the very individual users who generate the data thus leading to empowerment.

Examples of data empowerment

Some examples of data empowerment are elaborated upon below. These are intended to illustrate the variety of purposes, scope and underlying technological solutions that data sharing can take.

Skills and employment: In India, easy access to trusted digital records such as school degrees and transcripts enables people to prove their readiness for jobs. Not only does this offer the opportunity for employment among people who otherwise have few proof points of their skill level, it cuts out the industry of corruption around false certificates.

Health services: In Estonia, the ability to access personal data digitally is helping individuals better manage their health by creating a single, consistent health history that can be shared with all healthcare providers and by improving access to supporting services like filling prescriptions online, which is done nearly 100 percent of the time in Estonia.

Financial services: In China, personal data histories such as transaction histories and consumer behavior are helping people demonstrate their creditworthiness and gain access to lending in order to start or grow new businesses.

Goals of data sharing determine approach

The examples above describe a variety of approaches to data sharing that solve particular pain points. These pain points define the different approaches to data sharing (discussed in detail below). Governments need to decide not just what the purpose of data sharing is but also the data types that can be shared, the level of consent that individuals need to give to share data, and how data will flow between stakeholders.

Estonia and India represent different approaches to creating techno-legal frameworks for data sharing each stemming from very different original goals. Estonia’s data sharing solution was built to create efficiency in the citizen-government engagement and, in doing so, build trust among its citizens for the newly formed government following the separation from Russia. India’s data sharing solution has arisen with the intent to give the hundreds of millions of low-income people that are increasingly “data rich” specific opportunities to leverage their data to access improved commercial services such as credit and employment.

It is not surprising then that the approach each country has taken is different: Estonia is deeply focused on sharing government data to improve government service delivery whereas India’s approach is designed for sharing a range of government and commercial data to reduce transaction costs and therefore expand the addressable market for all types of commercial services. This difference in goals determines each country’s architectural approach so that in Estonia consent is not required for each instance of data sharing (because the government has clarified in law which government agencies have rights to view/use data). India’s solution, on the other hand, requires explicit user consent (and therefore a holistic consent architecture) to be established every instance data is requested. For more on consent see Figure One.

Figure one: Understanding consent philosophy

Consent is a much discussed concept and countries need define their own philosophy with regard to it. Consent is mostly commonly understood as given to platforms by individuals to collect their data, but there is another facet to it, the consent to share which refers to the individual ability to share their data in return for better goods and services which can lead to their empowerment.

Consent can exist on a spectrum, on one end it can be protected heavily by laws/regulations and on the other end, control can be given entirely to the individual to grant and revoke consent as seen fit. For example (explained in detail below), the Estonia data sharing platform requires individuals to give one time consent for data sharing, which is managed by the government data exchange layer. Whereas, in India, the burden of consent is entirely on the individual, who has to manage their own data, and data requests.

Irrespective of the frequency of consent, it should be reliable. It should also be non-repudiable, machine readable, digitally-signed and can be given for a variety of purposes such as defining the scope of data shared, verifying users and data processor, detail data access permissions and establishing data purpose. A robust mechanism to give verifiable data through electronic consent can make data sharing successful. While designing technology for consent, a useful framework to use is “Organs” which means open standards, revocability of consent, granularity of data for permissions and access, auditable consent and data flows, notification for users on any access of their data, and security by design. If consent philosophy and design is designed through this framework it bound to liberate data and empower people. philosophy and design is designed through this framework it bound to liberate data and empower people.

Estonia: X-Road

X-Road is a government created platform for interoperability between decentralized databases and a data exchange layer that can be used by both public and, increasingly, private entities. It allows querying of 900+ government and private databases. X-Road was built to improve government efficiency in delivery of services, and according to government data saves the country 800 working hours a year.

If a bank wants to verify a person’s address and income, for example, the bank can query the individual’s data through X-Road. X-Road first authenticates the identity of the bank employee requesting the data to ascertain whether she is allowed to access individual data. It also sets a window for access and validates the purpose for the data request, in this case let’s say it is a mortgage application. Thereafter, it routes the request from the bank to the Population Registry which stores address data and the Tax Department which has income data. X-Road logs and timestamps requests. Permission is granted to transfer address and tax data from the servers of the concerned departments directly to the data processor, the bank. The data is encrypted end to end, and after its used by the data processor, it is deleted from their server. Data is routed through several servers, in case of a breach or compromise.

X-Road ensures confidentiality, interoperability, evidential value i.e. digital signatures to verify source of data and autonomy, where law has determined which government parties have access to which data. Users have full view of who is requesting data and for what purposes. Medical data is not part of this data sharing, and is regulated differently. In other words, users do not control the usage of their data but have full transparency of the sharing and usage of their data.

X-Road is backed by a legal and organizational structure, protocol stack and software to realise the protocol stack. While the usage of government departments is free, private players have to a pay small fees to use X-Road. It is being used in several other countries such as Azerbaijan, Namibia, and Finland. X-Road also allows for free movement of data within countries in the EU.

India: Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA)

DEPA is a broadly a techno-legal framework that enables individuals to leverage their personal data for their own empowerment while maintaining privacy. DEPA is in its pilot stages in India but it brings forth an alternative data sharing framework from X-Road. In DEPA, consent is sought from individuals who own and control their own data. The purpose of DEPA is to give users control of their data and let them use it to generate value for themselves.

In DEPA, in the same example as above of banks requesting personal data to process loans, works a little differently. There is a consent layer called the account aggregator or in the case of DEPA, a data access fiduciary (DAF). These can be government or private entities, who are mandated by the government to serve this purpose. Account aggregators exist to empower the individuals. Banks request data from the account aggregators. Account aggregator, in DEPA, are domain specific, which is to say there will be different account aggregators for financial services, education, health etc. The data is federated, or not centralized in one server and requisitioned through a robust consent architecture, based on individual consent.

The account aggregator will verify the data request from the bank – both the officer requesting the data and the purpose for this request. Thereafter, this request is sent to the individual, who stores data in a digital locker or a service that enables Indian citizens to store certain official documents on the cloud. Through the account aggregator, the individual grants the bank to view their income statement for a designated amount of time. The account aggregator cannot view or store the individual data in DEPA, but this might be regulated differently based on contexts. Permission can be given by the user for viewing of data as well as storage, if required. The individual manages every such consent, through the account aggregator, who manages data and consent flows. Account aggregators or DAF are paid by the data processor for their services per transaction.

While India and Estonia represent different approaches to national solutions for data sharing as a result of different key objectives, there is yet a third model to note:

Models of governments creating the environment for competing entrepreneurial models of data sharing to flourish – a data sharing marketplace. This model works in countries that do not necessarily want to over-regulate the data sharing space but at the same time want to provide individuals with the opportunity to safely share their data. However, DEPA relies heavily on individual consent which can lead to consent fatigue or over-consenting, both of which are not optimal for data empowerment. For this, governments would have to provide similar protections to personal data through policy, technology and institutional interventions, while ensuring that no monopolies are built.

Several data marketplaces that have been built over the last few years and are slowly growing as an alternative to government led and managed data sharing. For now, these marketplaces are emerging in countries where regulation on data is limited, and the rights of the individuals are not explicitly protected. Examples of data marketplaces are Wibson, Data Coup, Digi.me etc.

Therefore, every country must define its own objective in pursuing a data sharing solution. The objective will not only guide the design and implementation but also then creates the framework for measuring progress and impact.

Checklist

- Bring together a multi stakeholder group to brainstorm the main objective of data sharing based on pain points and existing solutions

- Define the spectrum of consent and where your countries lies on it

- Locate the purpose of data sharing in existing laws and regulations

- Sketch out a data sharing model most suitable to your context

Risks of Data Sharing for Empowerment

Before discussing risks, it is important to understand that not building a framework for data sharing is perhaps the biggest risk.

This is because, as discussed above, data is being generated at great speed, and is increasingly being used to provide goods and services to individuals. Those without a data endowment, are likely to be left behind from the process of development. In this scenario, individual control over their own personal data is critical for a meaningful existence.

There’s no way to see into the future on how technology and uses of data may evolve. It is nevertheless important to consider risks and mitigation strategies which include designing a data sharing framework based on PACT. Beyond that, digital teams must be vigilant and prepared for any pitfalls, which can occur while designing a new system. Some known concerns include:

Over-consenting: One key risk is that citizens will ‘over consent’ – opt into sharing more data than what is ‘safe’ – their data in exchange for some reward, monetary or otherwise. User consent is designed to combat institutions strong arming or over-incentivising citizens to disclose their data.

Low adoption rates across stakeholders: Data sharing hinges on the assumption that commercial platforms and users will agree to part with data generated on their platform with other players. So far, many commercial players have maintained monopolies over user data and may not participate in a system that debases that their position. Similarly, low user awareness on data sharing and its benefits may lead to low usage

Decreased value of privacy: Citizens express frustration and unhappiness at the thought of losing their privacy. However, privacy has shown to take a backseat when a simple reward is offered. A Stanford University economist researched this digital privacy paradox between privacy preferences and choices. A simple incentive like pizza may cause a person to relinquish the protection of their personal privacy.

Derived data: Users may have concerns about sharing their personal data, since platforms can derive intelligence from data without the user knowing. For example, the user may consent to share kindle history with a platform which can be used to derive political views, a growing concern for individuals.

Beyond these, there are some broader social ethics to consider about the life and longevity of data and how it is impossible to change/modify data once recorded. Any misdemeanors or defaults recorded will remain on record and can impact the quality of services and goods received. While this is not a hard risk, but it is good to think about in the development of the data sharing framework

How can these risks be mitigated?

The data sharing framework built by countries should balance the risk and benefit to users. Mechanisms for data minimization, informed consent, clarity of purpose, and other security measures can help mitigate the risk. Focusing on user factors, as mentioned above, such as awareness will also make data sharing more useful for companies and users.

Strategies for risk mitigation will also be embedded in the policy and regulation framework, as well as the approaches to technologies. Countries should prepare a risk mitigation plan to identify areas of risk, and possible strategies to address them. Figure 2 describes possible strategies to mitigate the risks highlighted above.

Figure Two: Risk Mitigation Strategies

Over-consenting

- Transparency of purpose to ensure that users understand how their data will be used

- Increased user awareness and data literacy to ensure that people understand the value of their data

Low Adoption

- Policy and regulation can be framed to bring all data sharing within the ambit of the framework, and enforce penalties on any sharing outside the ambit of the framework

- Ensure protections and security to of personal data is safe, and build user trust in the framework and encourages usage

- Build incentives for businesses to use data sharing platform

Decreased Value of Privacy

- Build privacy protection in the law

- Design limits to data sharing and put sensitive personal data outside the data sharing framework

- Enforce penalties for infringement on sensitive personal data

Derived Data

- Ensure transparency log of all data requests and purpose for data usage

- Enforce penalties for any breach of trust or usage of data beyond declared purpose

What are the examples from existing data-sharing platforms and protocols where these risks have been encountered?

As mentioned, data sharing is new and the risks of sharing are still being grappled with. It is difficult to identify, in detail, how users are platforms that are actively involved in data sharing a preventing these risks but some examples are beginning to crop up.

For example, Accenture [3] has written out guidelines for data sharing with external partners for firms. The guidelines include ideas such as: develop an ethical review system, identify risks of data sharing early on, minimize data where possible, and emphasize on transparency when processes are not clear.

Similar thinking on data sharing has occurred in the health sector but there are no standards and solutions on how to deal with the risks of data sharing, in general and need to be developed urgently.

Checklist

- Identify risks to data sharing in your own context across users, corporate players and the government

- Prioritize these risks in terms of likelihood and extent of damage

- Decide redlines for each risk

- Understand the willingness of the private sector to participate in risk sharing

- Discuss mitigation strategies through an all-stakeholder meeting, develop risk mitigation plans

- Engage civil society organizations to inform users on risks

3 Designing an Approach to Data Sharing

Principles of Data Sharing

Thinking about data sharing begins with a discussion on core principles that will hold together the framework of data sharing.

Principles are critical to foster inclusive data sharing systems that place citizens and their rights at the center, and ensure that the ideas of agency and choice are clearly embedded in the data sharing system. Digital teams can interpret these principles in their own context and based on the objectives of their stakeholders, laws, considerations and most importantly, citizen needs.

Individuals must have clearly defined (legal) rights over their own data

Data generated by or about individuals legally and philosophically belongs to them, irrespective of the platform used to create the data. Individuals should have the right to choose who they provide access to their data and for what purposes. For example, health data is generated by the service provider i.e. hospital. If the hospital wishes to share this data with another entity, it must seek the consent and authorization of the user.

However, debates on control over personal data have been raging globally. Governments will have to legislate boundaries, define frameworks and rights individuals have over their own data and the limits to these rights. The most cited limit to control is in the context of national security, where this right can be revoked or for individuals who have been accused of crimes. Further, while defining data rights, responsibilities of platforms on which data is generated will also have to be defined which should include aspects of security and data protection, without which data empowerment cannot occur. Each digital team should aim to draw out the limits to user control over her data and the responsibilities of governments and corporates to protect this control.

Transparency by design

Platforms designed for users to share their data should aim to demystify consent, the use of data requested, and the method of sharing through clear guidelines on all aspects of data sharing for empowerment. Fundamentally, they should create transparent systems which allow users to control their data for e.g. all data requests and, purpose for data use is visible to citizens in Estonia through the transparency log. Only once this is achieved will the users be able to easily share their data and trust the system to safeguard it.

Digital teams should especially think about the extent of transparency and to whom its applicable. For example, while individuals should have full visibility on how their own data is processed, is it appropriate to have the same transparency on the data of other individuals? Similarly, digital teams need to consider the process of building accountability, both within and outside the government, and the mechanisms that need to be put in place for it for example, code of ethics, political oversight, redressal mechanisms etc.

Build data empowerment for scale

Data empowerment frameworks should be designed and built at scale, and such that they are applicable across stakeholders and industries. Building for scale adds efficiency and transparency to the process. When data sharing is designed for scale, it can benefit from national laws and regulations, without exceptions. Scaling should be done up i.e. from the local to the highest levels, across which is across government silos and out to the private sector. [4]

A common data empowerment system used at the population level will make it easier for users to be involved. This way, users do not need to navigate different systems and consent philosophies. Better value for citizens can be created, as data can be optimized and used to transform and innovate better goods and services for users.

Ongoing and proactive risk mitigation

Digital teams should understand the “harm” done through the leak or misuse of user data and pay close attention to where the framework can be vulnerable to these risks.

To do this effectively, digital teams should develop their own categories of harm, and develop risk mitigation plans accordingly. Risk mitigation strategies should be proactive, and should not wait for breaches. They should also define roles for different stakeholders – users, local governments, businesses, and civil society organizations to reduce chances of misuse of personal data. This sensitivity and proactiveness in risk mitigation and response will help reduce vulnerabilities of data sharing.

These principles are a way of re-balancing power between the state and corporates and the individual. These principles will have to be enshrined across the framework, in policy, technology and the institutions that govern personal data. Digital teams from countries have to align stakeholders to develop the principles and ensure that they are constructed through the prism of individual rights.

Checklist

- Define principles through a multistakeholder process – principles must reflect data sharing goals

- Through stakeholder interactions, adapt principles to reflect context. Stakeholders can include corporates, and citizen representatives

- Document findings

- Refine principles, if required

- Ensure transparency in process while designing principles

- Identify existing frameworks, tools, policies and technologies that help further principles of data-sharing

A Four-Pronged Approach

Designing a Parallel-processing approach

With a clearer sense of the pain points and the types of risks you must mitigate, you can more clearly imagine how you want data sharing to look and feel from the perspective of the individual.

To design any effective data sharing framework, a four-pronged approach is required.

Each of these prongs need to be working together in parallel — user readiness, policy and regulation, institutional capabilities, and data sharing technology.

Each of these components define the approach to data sharing and run simultaneously, in parallel, there is no prioritization or hierarchy among these prongs. For instance, India did not have a data protection policy architecture nor was there sufficient connectivity infrastructure or user readiness before it implemented Aadhaar, the biometric identity. Meanwhile, Estonia spent years building infrastructure and readiness, and slowly rolled out its e-governance infrastructure. Both countries developed the process of digitization based on their own contexts.

There is no prerequisite to data sharing. It can be built in countries that have robust policy architectures or user readiness, or in those that don’t, it depends entirely on what the digital teams consider priority and how the journey on data sharing should be constructed. These prongs are suggestions for an ideal scenario and not prescriptions.

These components also can be seen to have similar weightage and therefore similar impact on the success of data sharing, so it possible that one country prioritizes technological design and constructs a world class system for data sharing but does not invest in user readiness or institutional support, and therefore is unable to see success in its endeavour.

4 The Data Empowerment Framework

A Roadmap

Understanding Your User

Users are an integral part of data sharing. Their preparedness and ability to navigate their own personal data is key to building a framework that is empowering to them.

In many contexts users do not fully understand the potential value of their data and do not know how to protect it or exchange it meaningfully. For instance, research suggests that individuals consider their address, phone number, name and date of birth to be their most sensitive data but are also most willing to share this data in order to purchase goods and services. [5]

There are several user factors that will determine the success of data sharing and governments should aim to landscape these factors regularly to ensure that there is no exclusion from the data economy. Some of the most important user factors are:

Technological access

Digital infrastructure that moves population towards becoming “data -rich” is important. Without equitable access to technology and means to create data histories that can be exchanged, there is a risk of creating a “digital underclass” – that will be unable to engage in a data economy. A data divide can add to existing vulnerabilities and inequities in society.

Countries need to understand how technological access is distributed across the population. Simple distributions can include active users of feature phones, smart phones, mobile internet and computer internet. Similarly, for banking, there can be no bank account, bank account, mobile banking. While countries can develop their own metrics for technology access, it is important to get smart on these numbers to develop a strategy on how to bring all users to the same level of access.

There are lessons from India, a large country, with a largely poor population, that has been able to extend technological access to a majority of the population over the last decade or so. Through the efforts of the government and private sector, there are over 1.2 billion mobile phone connections, and over 500 million unique bank accounts. India has also built a unique digital infrastructure, as a public good, that has accelerated India’s digital progress.

Digital identity

In order for personal data to be shared across parties, there must be a common way to identify an individual’s identity with whom their personal data is linked. In other words, sharing an individual’s address data is only possible if the data processor and user have a defined way of specifying whose data is being requested and shared. Digital identity need not be a universal ID i.e every citizen must have the same identity, as in the case of India and Estonia, but that every citizen should have a form of identity. In the context of data sharing, it can make granting permissions easier.

Data awareness and literacy: It is critical that users have adequate amounts of data awareness as they begin to share their data. Awareness includes understanding the data one is generating through use of online platforms, protecting your digital assets, and knowing how data is used by platforms. All of this can be broadly defined as informed consent.

Beyond awareness, it is also important to build data literacy, which means understanding the insights that are available through your own data. This, of course, cannot be expected of everyone but it is important that data is presented in a palatable form to users, who can then engage with it better and understand its potential. This can include making data accessible for the user, for e.g. through visualizations. The process of making users engage better with their data can help democratize data practice.

Pain points

A key to success in introducing a new technological solution is to ensure the solution is solving a specific problem for users. It is useful to understand the situations where users would save time or money if secure, trusted data sharing were possible. This could be for verifying income data when seeking loans, verifying educational status when searching for jobs, or many other situations. Having a clear sense of the pain points will ensure you are able to maximize interest and adoption in the data sharing solution you design.

Institutional Functions

There are at least three types of institutional capabilities or functions that need to be established in order to ensure data sharing solutions are secure and effective and leads to empowerment. These are: supervisory, fiduciaries, and redressal functions. Many countries may have institutions or regulators that perform some of these functions, but it is important to bring forth these capabilities and map them to the needs of data sharing for empowerment.

Depending on preference and goals of data sharing for empowerment, it is possible to set up one singular institution that performs these functions, or have different sector specific institutions as in India, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (for telecommunication), and Reserve Bank of India (for banking) and an overarching body for data protection.

Supervisory functions

Data supervisory functions must be defined to establish consistent application and enforcement of data sharing rules and regulations across government and the private sector. As mentioned above, it is possible that institutions in countries are already playing this role but their roles, power and processes have to be clarified and organized.

To operate effectively, supervisory functions must at a minimum be founded through laws and regulations that govern data. Along with their defined roles, institutions carrying out these functions must be funded as an independent authority and have clear accountability to all stakeholders. It is possible, that each sector has its own overseeing institutions, which can also take up supervisory functions.

In the European Union, GDPR mandates that each member country establish Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) that “supervise, through investigative and corrective powers, the application of the data protection law. They provide expert advice on data protection issues and handle complaints lodged against violations of the GDPR and the relevant national laws.”

As an example, the Estonian Data Protection Inspectorate defines its role as defending an individual’s constitutional rights to 1) obtain information about the activities of public authorities, and 2) inviolability of private and family life in the use of personal data; 3) right to access data gathered in regard to yourself.

Account aggregator functions

Account aggregators facilitate the exchange, storage and alteration of data between entities and individuals and entities. They can, in principle, be any entity – the State, an individual, a commercial group – that has authority to mediate flow of consent and data. Beyond this basic function, the roles and responsibilities of the account aggregator depends on the goals of data sharing.

Account aggregators play several roles. They manage consent and data flows, verify data, quality and purpose for request, mediate the relationship between the user and data processor. The account aggregator may or may not, as in the case of DEPA, have access to personal data and in most existing models, unable to store it due to encryption. In the private sector models, usually there are users , data processor and a version of the account aggregator. These account aggregators verify the users information, quality and trustworthiness and if required, arbitrate between the user and data processor, similar to the trust services in X-Road and the account aggregators in DEPA.

Account aggregators can either be subsidised and run by the government or be independent private businesses. This function can be embedded in existing sector specific institutions.

Redressal functions

Redressal functions are required to process the complaints and concerns of individuals and corporates, in the context of data sharing, where required. This can help stakeholders use data sharing more effectively.

Redressal systems should be created at different levels, such that decisions can be appealed if required. Redressal functions, like supervisory ones, should be embedded in independently funded institutions.

In Estonia, the data protection inspectorate (DPI) provides legal enforcement for upholding data privacy, and serve as an ombudsman and preliminary court. The DPI ensures that citizens can lodge complaints against public sector institutions, and receive impartial counsel.

In the Indian data protection bill, has provisions for grievance redressal. The data protection authority is entrusted with this responsibility – to address any citizen/business issues of violation. Regulators in different sectors, such as the telecom regulator in India, have been addressing grievances and a similar entity is required for data protection and sharing.

Technology Options

The technological design of the data empowerment framework must encompass the principles and goals decided on by the digital teams. However, any technological design should be responsible and built such that it enables users and data processors to successful participate in data sharing for empowerment. Some of the key ideas that should be represented in the technology are:

Technology as public goods: Technology specifications should be available as a public good i.e. created such as that it is non-rivalrous and non-depleting. Technological should be built to be inclusive, and for universal access only then can it useful for data empowerment.

Minimalism: The technological aspect of the framework should be be minimal. It should not have too many requirements and be easy to adopt and build off. This is particularly important for a data empowerment framework so that it can enable innovations from different entities, and simplify the user interface required for its success.

Open APIs: The framework should provide open and standard set of application programming interfaces (APIs) for participating in data empowerment. These APIs should be minimally prescriptive, and should be available to access (as public goods) for anyone working on data empowerment to utilize. Open APIs can enable safe sharing of information, reduce the barriers to entry to data empowerment and foster innovation.

Privacy by design and transparency: Assuring users of the privacy of their is data is critical for participation as well as empowerment. Technological design needs to be built with privacy at its center. This means, user data must be protected without requiring any input or action from them which is that privacy should be the default, functionality for users should be minimally affected by the privacy protection, which means that errors/usage will not degrade privacy and privacy should be guaranteed from collection to use of data by the data processor. Technology also has to ensure that user privacy is balanced with transparency of government and companies.

Scalability and evolvability: Technology should be built such that it can be build up to deal with different levels of growth of usage. As mentioned above, the entire framework should be designed keeping scale in mind. Technology should also be evolvable, which means it should be adaptive to new situations, and be able to accommodate multi-objective functions. These two features of technology make it more reliable, and more affordable to be built as a public good.

User tools

Beyond these key ideas, technology should also make the user experience more intuitive and safe. In the existing data sharing technology as seen in DEPA and X-Road, some examples of effective user tools are seen.

Digilocker (DEPA): Digital locker is a service operated by the government of India. Users can store official, verifiable documents in the locker, and provide consent to government and non-government bodies to view documents for a defined amount of time. The Digilocker is critical to DEPA, as this gives the user control over their own data and documents, and allows them to consent access to whoever they choose.

E-Services Portal (X-Road): The state e-services portal allows citizens of Estonia to access various e-services of the government. The portal is logged into through the secure e-ID. Through this portal, not only can citizens access governments services with ease, but also view who is accessing their data, and for what purpose.

Policy And Regulation

Policy and regulation is the backbone of a robust data sharing framework. It allows digital teams to define the possibilities of data protection while providing protections and rights to users of technology. Robust policy and regulation can create the space for innovation while ensuring the users are empowered and not exploited by technology.

Policy and regulation for data sharing needs to develop a country-wide understanding on several areas such as

Data rights which deal with the individuals right over their own data and touches upon issues such as transparency and modalities of control over data, revocability, right to correction, right to be forgotten and the limits to these rights.

Security of processing personal data which includes encryption, confidentiality, data storage, notifications for data breach, and maintaining awareness of individuals

Transfer of data to third parties which deal with binding rules, safeguards, and grounds for usage.

Supervision authority, and its independent status, tasks, powers, activities and accountability.

Remedies and penalties that carve out redressal mechanisms for users, define compensation for individuals, enforce penalties on delinquents, and define any judicial remedies, if required

In Estonia, the policy, regulation and law was framed focused on the digital economy. Access to internet was guaranteed by law, as were the various protections to users. The law defines, for instance, permissions to collect data which needs to be approved by data authorities, access of data, rights of individuals on their personal data, penalties for manhandling data and how data is labelled and stored. As a result, citizens feel protected by the law, and trust the government and other authorities with their data. This makes for a safe and secure environment for data sharing.

At the same time, in India, there were no policy or regulatory frameworks in India as digitization gathered pace. The rights of the individual on their own data were not defined clearly, the responsibilities of corporates and the government were also unclear and no redressal/appellate were put in place. As a result, there was massive exclusion from government programs, misuse of government databases and breaches were recorded. Now, India has developed a draft data protection law which is being discussed in the parliament and is likely to solve for some of these issues.

Each country has its own process and priorities. As mentioned before, it is the purpose for data sharing that digital teams decide will govern the structure of policy and regulation. If the purpose for data sharing is to build a data sharing marketplace then there would be limited laws and users would be given complete discretion and control of their data. If the purpose was improving health access, then the sensitivity of health data would become the primary feature of data sharing policies and regulation.

Finally, policy and regulation should be developed through a consultative exercise, which consults not just industry and government players but also the voice of the users, so that their opinions can be reflected in the codification of use of technology for data sharing.

5 In Practice

Implementation Tactics

Even when the entire approach is in place, the success of a process comes down to implementation. Given that data sharing is a complex idea, and one that requires different stakeholders to collaborate, its implementation becomes even more tricky. These are tactics governments successful in building a digital economy have adopted which can, as mentioned above, be interpreted and contextualised through the process of designing a data sharing framework. Some of the most effective implementation tactics are as below:

Political will: Data sharing may not be interpreted as a idea government’s adopt immediately, as it means surrendering part of the control over user data to individuals themselves. Therefore, political will, which translates into an understanding of the subject and a motivation to implement it becomes critical. Data sharing needs a political champion who can mobilize different stakeholders and inspire them to participate in the data empowerment of individuals.

Clear leadership: While designing data sharing, there needs to be a clear leader for the project who can coordinate the effort and make sure the framework is aligned across stakeholders. This is especially important since data collection, storage, sharing and processing is done differently across departments in the government and private companies.

Multidisciplinary teams: Due to the complexity and multifaceted nature of data sharing it is important to involve multidisciplinary teams in the process of defining the policy, technology and institutional framework. These teams can interpret data sharing from legal, political, social, ethical, economic and technological angles, and make sure that the design of the framework is useful to all, especially the users. In the absence of multidisciplinary teams, frameworks can tend to miss out on small nuances that can have grave consequences over time.

Local capacities: It is important to find government officials as well as private citizens, and corporate teams, on the ground who understand data sharing, and are able to explain and onboard people in the country. In India, for example, with its poor digital uptake and literacy, young adults have become significant to the process of building comfort with digital technologies. Such groups of people must be found and their capacities built regularly.

Simplicity of design: The design of the framework must be simple and easy to understand, only then adoption will occur swiftly. Simplicity can be embedded across policy, technology and institutions such that data sharing can be understood and implemented.

Collection of feedback: A robust feedback loop should be designed for all stakeholders to regularly give the data sharing leadership information from the ground, so that the design can be modified regularly.

Communication and reporting: Through the institutional actors, a communication and reporting system should be built, such that the processes are chronicled and transparent and so that ambiguity of process and decisions is reduced.

Measuring progress toward technology access and user capabilities

There are ample resources on the role of government in promoting technology access and end-user capabilities. This guide will not elaborate deeply on these points as other resources are already available.

However, per any effective roadmap, we strongly suggest developing indicators against which progress can be measured. The European Union’s DESI (Digital Economy and Society Index) establishes indicators on digital competitiveness which may be helpful. These include: deployment of broadband, quality of broadband, quality of mobile data service, and others. As mentioned before, countries must decide what their own measure of technology access.

Technology access is not just limited to the availability of infrastructure, it also includes digital adoption and usage by different stakeholders. For the government, digital usage can be measured through level of e-government or what degree of government services are provided online. For example, according to the UN6 e-governance index, 176 countries provide online education services in education and 152 countries provide these services for health. For businesses, level of digitization can be measured through level of use of digital in business processes. The EU includes indicators such as use of business software for electronic information, sending electronic invoices, social media engagement with customers to define digital integration of enterprises.

Digital infrastructure and usage needs to be prioritized by the government and needs the involvement of the private sector. In Estonia, the government took the lead in ensuring broadband similarly in India, the government has set up a Broadband Network Limited which is mandated to create a National Optic Fibre Network, and reach 250,000 villages across India. For digital integration in government, the Government of India, has moved all transfer of government benefits and entitlements to online platforms through the direct benefits transfer portal. Similarly, in an attempt to digitize businesses, the

Similarly, end user capabilities can be measured using different metrics. Such as access to broadband/internet connectivity which is covered under technological access. Other facets is actual usage of digital platforms and services such as participation in social media, use of e-commerce, digital financial services, use of applications for transportation etc. User awareness also needs to be measured for this indicator. User capabilities also includes access to a digital identity – which can be biometric or in the form of a smart card.

Each country will have different levels and measure of user capabilities, and must decide the kind of investment that is required for it. For example, Estonia spent significant time and resources building user engagement with digital, it had the advantage of digitizing processes much before other countries, and was able to invest in access to broadband, user awareness and capabilities. By 1996, Estonia had mandated internet access and training in schools and soon after established internet access as “social right” which meant that the state was providing free access terminals in public places across the country. Meanwhile, India decided to introduce digital identity before initiating users.

Both are different approaches that reflect the context of the countries i.e. Estonia has a relatively small population, that is literate and digitally onboarded, but India’s large and heterogenous population makes it difficult for the government to do a comprehensive push on user capabilities, as this would lead to delays. India’s assumption was that as the technology becomes more ubiquitous and people see the value in its use, the government and market forces would be able to improve their capabilities.

A Final Note on the Importance of a Robust Civil Society

Civil society has a critical role to play in the building of a robust data sharing framework that prioritises the needs of users, and views it through the prism of rights and empowerment. Civil society is the only stakeholder that can bring forth the lived experiences of people and the impact of technology on their lives, as they navigate both the idea of the value of their personal data and how to share it effectively. Technology can tend to be mystifying for people, and there is danger of being exploited because of lack of understanding, access or awareness – civil society organizations can help mediate the relationship between people and the rapid ubiquity of technology in their lives.

Civil society organizations, working across sectors, can serve as a bridge. They can help hold governments and private companies accountable for their actions, and translate the needs and concerns of people. Civil society organizations can also help build buy-in for new technologies and policies on the ground and ensure greater adoption and success.

Therefore, civil society organizations, must be a key stakeholder to any countries journey towards data sharing. They should be part of the process from the beginning, consulted at every step. In India, during the net neutrality debate, the government opened its proposal to open consultations across the country. Rights activists, academics, technologists, entrepreneurs as well as regular citizens concerned about the issue participated in open dialogue with the government. It was a long but meaningful process which resulted in one of the most progressive net neutrality regulations in the world, which put the rights of the user at its heart.

Data sharing is an ongoing conversation, it is new and its details and potential need to be unpacked further. Civils society cannot be ignored in this process. It is essential to have a representative of the people, to bring forth their voice and experience to the construction of a framework that can define their lives.

Digital teams across countries need to develop processes for engagement and dialogue with a wide array of civil society organizations, working across issues and sectors. Their contribution will be critical not just to understanding the user but developing a framework that is useful, and delivers on the goal of data sharing i.e. to empower individuals with their own data.

Definitions

User: An individual in the digital economy generated personal data through platforms.

Data Processor: A digital platform users that provides information, goods and services in exchange for personal data that is either given voluntarily or generated through of the platform

Account Aggregator/Data Access Fiduciary: An intermediary between the user and data processor who manages consent and data flows for data sharing.

Digital teams: Policy teams within governments focused on building a responsible digital economy.

Further Reading:

Information Fiduciaries and the First Amendment

Electronic Consent Framework, India

Wibson, Decentralized Data Sharing

[1] From Extraction To Empowerment: a Better Future For Data For Development, World Web Foundation (2018) retrieved from https://webfoundation.org/2018/05/from-extraction-to-empowerment-a-better-future-for-data-for-development/

[2] Improving Customer Experience Through Customer Data, Newman, D; (April, 2017) retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/danielnewman/2017/04/04/improving-customer-experience-through-customer-data/#14da8dc74e64

[3] Accenture Labs, The Ethics of Data Sharing: A guide to best practices and governance (2017)

[5] Quin, M & Rogers, D; What is the Future of Data Sharing: Consumer mindsets and power of brands (October, 2015)

![]()